‘The Rotterdam Way involves embracing innovation. The Rotterdam Experiment is an accelerator of change and our contribution to the recovery of our industry.’ Catherine Kalamidas, Account Manager Congresses at Rotterdam Partners Convention Bureau opened the second edition of The Rotterdam Experiment about gamification, which took place on 18 February.

Yuri van Geest gave an insightful presentation and then Catherine welcomed experts for a roundtable discussion to delve further into the topic of gamification in an attempt to answer the question, ‘What will your event of the future look like using gamification.’

According to Catherine, ‘Think about your own youth and the life lessons you learned playing games. Perhaps you gained knowledge about how to make a deal playing Monopoly, problem-solving by playing Clue, strategic thinking by playing Battle Ship, collaborations and creativity by playing Dungeons and Dragons or developed a sense of timing and dexterity by avoiding ghosts in Pac-Man. Examining these learning experiences, you have sufficient insights to implement gamification successfully for your event.’

The past year has forced us to reassess our personal and organisational priorities. Some of the analysis areas include the need for wellbeing, mindfulness and self-awareness, values that weren’t as widely present pre COVID-19 but are now entering our working culture going forward. This new set of values brings significant opportunities for the gaming industry and events.

Why use gamification?

Now, after one year of hosting and attending virtual events, the events industry is facing the challenge of how to engage attendees and combat ‘zoom fatigue.’ The first speaker, Farshida Zafar, L.L.M., Director ErasmusX at Erasmus University Rotterdam and Senior Fellow Jean Monnet Centre of Excellence for Digital Governance shared an example of building four campuses of Erasmus University in Minecraft.

They chose the gaming environment to first create interaction with their core audience (students) and immerse future and current students in campus life and for them to engage with each other. Second, through gamification, they activate people to do something instead of being passive.

Farshida concluded, ‘Gamification enables a sense of bonding. When people play a game, they have a common objective or goal, and that brings them to a state where they want to succeed in this activity.’

Gamification doesn’t need to be engaging

How many times have you been asked to sing, do yoga, or participate in quizzes during virtual events while all you wanted was to remain passive or use the time to answer some work emails? People engage differently, and the good news is that gamification and engagement can go unnoticed by participants.

According to Teresa de la Hera, Assistant Professor of Persuasive Gaming, Department of Media and Communication at Erasmus University Rotterdam, ‘Gamification doesn’t need to be always about fun or engagement. It’s about using digital game mechanics to achieve a specific purpose. It’s important to take into consideration two goals. One, the serious goal—what is the goal of my event, and what do I want to achieve? Second, how should I align my gamification goal in order to support my event goal. The gamification goal could be a competition, discovery or other specific challenges. And we need to consider how both should be combined in order to support each other.’

Teresa shared, ‘The best gamification is that which is unnoticed. This is when gamification elements are supporting the serious goals. A common example is booking websites. The gamification strategies on these websites endeavour to make us book as soon as possible. It’s not about fun but to make us book.’

According to Teresa, there are four dimensions of game theory that can help us think about gamification from a broader perspective:

- Game design, interface and pattern: This involves the gamification basics that are applied to leader boards, points and badges.

- Game mechanics: There are common game mechanics that include limitations of time and resources; for example, when you can have a one-minute chat with a panellist. This limitation can provide more motivation to learn about the panellists, read their profiles etc., to pick the right person to talk to.

- Game models: When we think about gamification, it’s typically connected to competition. But games are not always about competition. They sometimes involve discovery and curiosity. Think about event programmes, which can be boring, and perhaps an alternative—an interactive map to discover different event spaces we would love to attend would be a better alternative when designing the programme.

- Design principles: This aspect concerns participants’ needs and the game being able to adapt accordingly; various types of games and events for different participants.

Purpose-driven gamification – Odyssey/Momentum case study

A hackathon is an excellent example of purpose-driven collaboration. Christel Sieling, Director of Operations at Odyssey, shared how they’ve pivoted their live hackathon, called Momentum, into a virtual format in 2020.

They faced the task of enabling an eco-system for over 1,500 people spread all over the world to work together and collaborate to solve complex challenges. The visual platform was built for mass collaboration and is an integrated open 3D world that turns collaboration on challenges into a unified, effective and playful experience for everyone.

In numbers: there were 21 challenges, 100 teams, and over 1,600 participants from more than 60 countries collaborated in the same space simultaneously; 92 prototypes were delivered after 48 hours.

The challenges included a fossil-free future, conflict prevention, conscious cities, internet of logistics, healthcare, public safety and security, outcompeting destructive systems, nature 2.0, opening up real estate, self-sovereign identity, energy singularity, sovereign nature and generation now.

Asked about the challenges in creating Momentum, Christel shared, ‘When bringing the hackathon online, everyone’s success depends on their ability to connect and collaborate with other people. However, collaboration remotely or online is highly fragmented. How can you see who is working on which challenge, and how can people join and contribute to these challenges? Further, there’s also the so-called flat web problem; currently, online collaboration is performed within the flat web. We navigate the web through clicking and scrolling, but there’s no real sense of agency, spatial awareness or presence of anything or anyone. While we are in the transition of attempting to solve these complex challenges, you want to take people along on the journey and move them to collaborate together. That’s the issue we’re endeavouring to crack in creating Momentum.’

Collaborating on such complex challenges requires ‘moving away from ego-systems to eco-systems with all the players.’

Christel continued, ‘Creating Momentum was inspired by computer games such as Fortnight and Minecraft. In the beginning, we looked at what was on the market and saw that many online event platforms attempt to mimic real life. Offline, we created a highly artistic experience that got everyone into a collaborative mindset. We used meeting design to do that, which already had some gamification elements to it. And we really wanted to bring that online. That’s when we began to look at massive multiplayer games; this inspiration enabled us to bring collaboration into the metaverse, and we started building momentum.’

Gamifying a conference – ShipCon case study

The second case study presented at the Rotterdam Experiment was by YoungShip Rotterdam. Anne Geelhoed, Vice-Chair at YoungShip Rotterdam, shared how they pivoted their bi-annual conference—ShipCon—into a virtual format. This event is specifically aimed at young maritime professionals, with 30 chapters across 6 continents, and besides the serious goals for the event, it had to be energising.

According to Anne, ‘Taking a conference online brings its own challenges (e.g., a shorter attention span of the participants, how to ensure sufficient interaction and networking). These considerations had to be taken into account before choosing a format.’

For the 2021 edition, the ShipCon organisers decided to spread the two-day event into a two-week online conference, incorporating gaming elements. The game will begin after the kick-off and will work towards the end game two weeks later. In between, there will be themed nights addressing sustainability, digitalisation and diversity. These themed nights will be two hours long and will also include a keynote speaker, presentations and panel discussions.

Anne shared, ‘We were seeking a way to make an online event interactive, engaging and stimulate participants to get to know each other and work together. Gamification elements could help achieve that aim; for instance, by making it competitive, with teams competing against each other and against the clock. This approach would spark enthusiasm and also the competitive drive that people have by nature. Additionally, by forming teams, people will get to know each other—there’s the networking element. And by working towards a mutual goal, attendees are ‘forced’ to collaborate. That would also help the sponsors, who will submit a case and will have young professionals thinking about that case.’

YoungShip also included collaboration with other parties in Rotterdam to make this event happen. Anne shared, ‘ShipCon will coincide with the Rotterdam Maritime Week. We are working together with other young professional associations to broaden the audience and also with more established festivals in Rotterdam.’

One of the advantages of spreading the event to two weeks and creating shorter interaction moments is giving the sponsors more of such moments with the participants. That’s an opportunity that comes with gamification.

Destination Rotterdam will also be incorporated into the virtual experience. In the last part of the game, a live attendee will be steered by the virtual team to guide them through the city. That’s what a future event should involve—providing physical elements to the online game and incorporating a destination experience.

Involve all your stakeholders in gamification

In events, we need to ensure that all our event stakeholders are happy, and we must bring them on board. The interview with Alexander Whitcomb, Operational Manager ErasmusX at Erasmus University Rotterdam, explored how to bring stakeholders into the gaming environment.

According to Alexander, ‘First, you consider who your key stakeholders will be, why they would care about interacting with your game design and what problem would you be solving for them when they engage with your game. Second, what is the purpose of your game, and what are you trying to achieve with building a game? Organisers need to have a crystal-clear purpose. In the case of the Minecraft environment and Erasmus university, the added value of this game stimulates creativity. Rather than writing text down, it gets the students thinking more creatively and conceptually about what they will present.’

Alexander highlighted a particularly important point that many event planners have experienced by now—any platform has its limitations, and there’s no perfect platform. ‘When examining the platform to gamify the environment, many options are available. We chose the Minecraft environment because the platform is low threshold and known among the target audience (students). There are always limitations; so, you need to think creatively when designing your gamification. You can get around the limitations, but you need to know what’s important and critical to have and what is nice to have.’

The Experiment

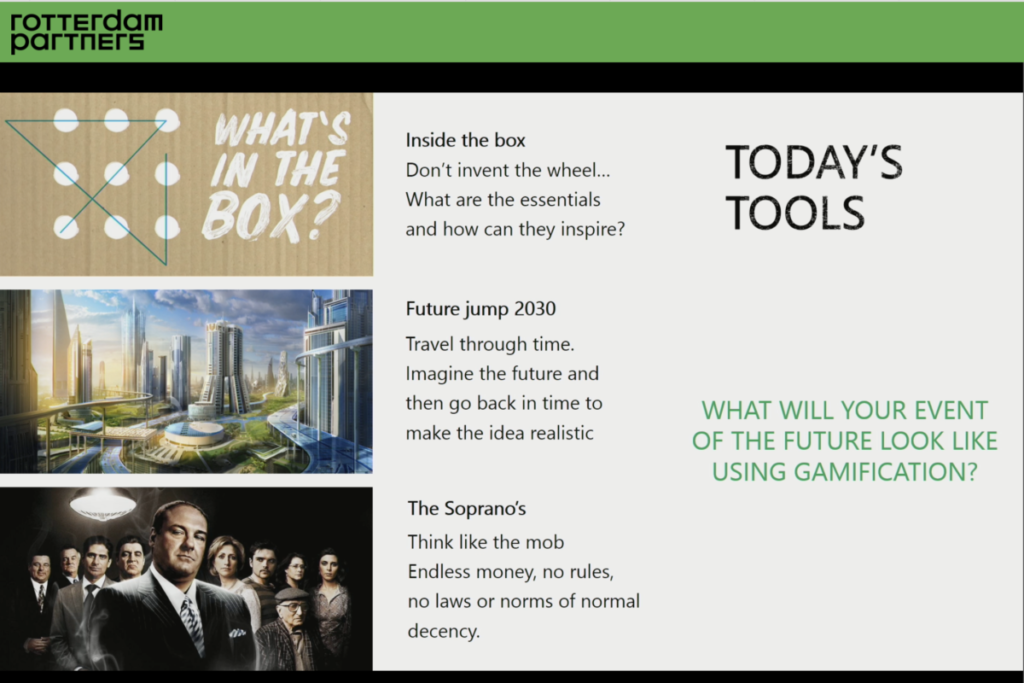

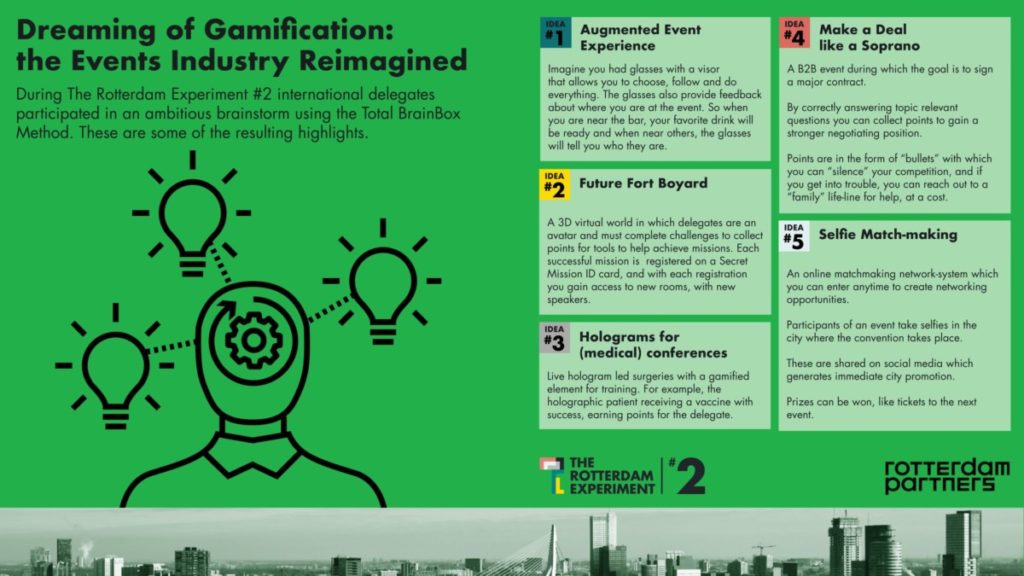

To bring all these theories into practice, Andries van Vugt—Founder & Creative Designer at Organiq—conducted an experiment. He brought the participants together to collaborate, network and develop ideas for a new event format, attempting to answer the question: ‘What will your event of the future look like using gamification.’

We used the TotalBrainBox method, a fun approach that helps to open the mind and think about new ideas and ways to answer questions. This method combines inbox and outbox thinking.

Inbox involves using a closed-world approach within the problem. The participants need to configure the essential elements of the problem situation and use them for a solution. Attendees must take the essentials of a certain problem area (e.g., events – entrance, lights, ticketing) and then take one of the essential elements and rephrase the question, ‘How could lights help us make a gamified event?’

Outbox involves going as far away as possible from the problem situation. Attendees must create seemingly crazy ideas and then head back home to make them realistic. For example, the question this time will be, ‘What would your event of the future look like using gamification in 2030?’ But then, they must return to reality, and within this crazy idea, there will be highly interesting parts that can be made realistic in the present time.

One of the tools used was ‘The Sopranos’. This strategy involved thinking like a mob, with participants having endless money and no rules, laws or norms of decency. Anything is possible being a criminal. For this group experiment, we were divided into breakout groups of 3–7 people whom we had not previously met, and we had very limited time to develop creative solutions.

One of my colleagues, who attended the Rotterdam Experiments but was in a different group than me, shared their event idea for a trade show where no rules apply, ‘TRADE UNFAIR’: the gamification of a trade fair against the clock. The concept was created by Robert Dunsmore, Gwen and Deidrick.

The idea:

One trade fair, unfair rules, one contract, one winner takes all.

Suppliers vie to lie, trick, trip and knock one another out of the game until the last man or woman standing takes everything in a Sopranos style. Electronic gamification of a trade fair would require an app at the heart of the electronic market to show the game’s progress, get to the top of the market and win the contract. The contestant or team with the highest stock index valuation and most points wins the trade-unfair contract.

The same app on-boards all contestants with the most contract details, and for all competitor profiles on board, truths or lies are their weapons. On the Sopranos theme, our points will be referred to as ‘bullet’ points. Suppliers taking part in the trade-unfair compete in the market game to lie, beg, borrow or steal to gain more ‘bullet’ points to move up the leader board and mute (or kill off in Sopranos style) their competitors’ chances.

All the game data sits on the hand-held app. However, the setting for the trade-unfair is a giant, immersive LED video hall built inside a traditional trade fair venue. All participants, suppliers teams and contract handlers are released into this giant, six-sided LED video ‘bear pit’ set. An immersive trade-unfair market is set with the app info scrolling around over and under the competitors’ feet, bathing them in data and electronic light, the countdown clock and the leader board market index.

Act on data from the bear pit LED walls, ask questions of other competitors and find and question the contract handlers for intelligence. Game information out of your competitors, and win plus ‘bullet’ points to climb up the leader board and increase your stock valuation. Trick or lie in a Soprano style to steal ‘bullet’ points off your competitors. Gain more plus ‘bullet’ points for discovering contract handlers and intelligence. Minus ‘bullet’ points for being tricked, truthful or careless are deducted; your stock valuation drops, and you fall down the leader board.

All game activity appears on the app and scrolls on the bear pit giant LED walls, ceiling and floors, along with leader board logs’ progress and failures. Lifelines are issued for failures, but at a cost—the top-three leader board contestants win Soprano-style powers. They can freeze weaker performers by ‘drugging’ (muting) their approximately, taking them out of the game for a couple of minutes or ‘kill them off’ (knocking them out of the game) by buying all their ‘bullet’ points if they have double the index/market valuation.

The winner is the last supplier standing or highest stock index valuation and top of the leader board at the time limit and wins the trade-unfair contract and all the money.

At lights up, an after party will be held for all contributors to come together with Sicilian wine, Grappa, food from the Sopranos cookbook (there is one) and an after-event awards ceremony—best liar, best trick, best mute, best deal etc., where each winner gets a ‘Tony’ award.

Further event ideas created by event participants:

Personal reflections

This experiment provided answers to some of the questions I’ve been thinking about in recent months.

First, how is it possible to engage large audiences with virtual events? From hosting and attending virtual events, I’ve experienced that it’s easy to engage a small group where everyone has a chance to talk or contribute. However, what about the larger events that seem to be more a ‘broadcast’ rather than collaboration? I attended large-scale virtual events in 2020, including the Web Summit, Tomorrowland and Abobe MAX. They used excellent platforms, but the engagement element was missing for me.

Both Christel Sieling and Anne Geelhoed highlighted the important aspect of not trying to replicate the live environment into the digital one. Rather than hosting a 1:1 supplier appointment, perhaps it would be better to place buyers and supplies into the same hackathon group and endeavour to solve industry challenges or give buyers the opportunity to work on a supplier case. Another favourite virtual networking method is the ‘networking roulette’, where attendees are matched with each other randomly on a video chat for three minutes. In regard to content, instead of offering multiple hours of live-streamed content in two days, it may be better to spread the event over two weeks and allow attendees to reflect on the sessions and be better prepared for the next ones.

The second aspect is to move away from the traditional event duration that we know from live events and prolong the event. We should stop thinking ‘inside the box’. As in the Sopranos method, no rules apply. Why should a virtual event be two days long when it can be two weeks or two months long? That approach would provide more space to collaborate, network and bring bigger value for sponsors.

Third, we need to distance ourselves from ‘gimmicky’ gamification elements and create events with more purpose and legacy. Let attendees contribute to creating an impact. Organisers don’t necessarily need to announce gamification elements but instead incorporate them into the event design and attendee journey. I now realise that gamification that comes naturally, rather than being forced, is more welcomed by attendees and will increase engagement rates.

Fourth and last, make the destination part of your gamification experience. That’s what we’ve seen with ErasmusX and ShipCon, which are held virtually in Rotterdam. Currently, with events and studies occurring remotely, I think it’s still important not to forget the ‘physical hub’ that we’ll return to when we can travel again. This strategy will add a visual dimension to the event, sparking curiously and exploration, all of which are part of gamification.

I got my answer to the question, ‘What will your event of the future look like using gamification.’

And what will your event of the future look like?

Watch The Rotterdam Experiment aftermovie:

No Comments